The theme for this week is life in the Word.

The selected passages: Psalm 119:105-112 • Genesis 25:19-34 • Romans 8:1-11 • Matthew 13:1-9, 18-23

- The call to worship Psalm expresses confidence in God’s word even during life’s severe afflictions.

- The Old Testament reading from Genesis recounts the birth and struggle of Jacob and Esau and of Esau selling his birthright to Jacob out of fear of death.

- The epistolary text from Romans strikes a confident note where the fear of condemnation is removed in Christ.

- The Gospel reading from Matthew includes Jesus’ Parable of the Sower dealing with people’s response to the word of the kingdom.

SPEAKING OF LIFE

- Title: Death is Short

- Presenter: Greg Williams, GCI President

- Text: Psalm 119:105-112

From the transcript …

The older I get the more I can relate to the statement, “Life is short!” It seems it was just yesterday I was a child in my parents’ home. Now if there is a child in my home, it is probably one of our grandchildren. Amazing!

It’s a sobering point of reflection to know that most likely, I have fewer days to live ahead of me than the ones I lived behind me. Yes, life is short.

However, for an episode of “Speaking of Life,” this is starting to sound a bit morbid. So, in thinking of the phrase “Life is short” from a Christian perspective, maybe we should change it to say, “Death is short.” After all, that is more accurate to our situation and our theology. As soon as we are conceived in the womb, we begin our inevitable march to the tomb. And, compared to the eternal life waiting for us beyond that point, it is a short march whether it be one year or a hundred years.

This is the biblical way to look at our present time when the clock and calendar seem to speed up. We don’t have to live frantic and fearful lives as if life is short. We can live each day fully in the peace and hope that comes to us in God’s word of resurrection life. That Word has come to us in the life and death of Jesus Christ. It was Jesus who took upon himself our march of death from the womb to the tomb and gave death a proper burial in the end. Death no longer has the final word on our lives, God’s word to us in Jesus does.

On that basis, we can live each day, no matter how dark the shadow of death may appear, trusting and being renewed to joyful life by God’s faithful word to us. Here is a portion of Psalm 119 that pictures this orientation in our short march on this side of the grave.

Your word is a lamp to my feet and a light to my path.

I have sworn an oath and confirmed it, to observe your righteous ordinances.

I am severely afflicted; give me life, O Lord, according to your word.

Accept my offerings of praise, O Lord, and teach me your ordinances.

I hold my life in my hand continually, but I do not forget your law.

The wicked have laid a snare for me, but I do not stray from your precepts.

Your decrees are my heritage forever; they are the joy of my heart.

I incline my heart to perform your statutes forever, to the end.”

Psalm 119:105-112 (NRSV)

He does give us life – he gives us eternal life. It is in this life that his decrees and statutes give us joy – forever. Thanks to God’s grace, the older I get, the more I realize, “death is short,” and eternity with Christ is forever.

I’m Greg Williams, Speaking of Life.

SERMON REVIEW

In Christ

Romans 8:1-11 (ESV)

There is therefore now no condemnation for those who are in Christ Jesus.[a] 2 For the law of the Spirit of life has set you[b] free in Christ Jesus from the law of sin and death. 3 For God has done what the law, weakened by the flesh, could not do. By sending his own Son in the likeness of sinful flesh and for sin,[c] he condemned sin in the flesh, 4 in order that the righteous requirement of the law might be fulfilled in us, who walk not according to the flesh but according to the Spirit. 5 For those who live according to the flesh set their minds on the things of the flesh, but those who live according to the Spirit set their minds on the things of the Spirit. 6 For to set the mind on the flesh is death, but to set the mind on the Spirit is life and peace. 7 For the mind that is set on the flesh is hostile to God, for it does not submit to God’s law; indeed, it cannot. 8 Those who are in the flesh cannot please God.

9 You, however, are not in the flesh but in the Spirit, if in fact the Spirit of God dwells in you. Anyone who does not have the Spirit of Christ does not belong to him. 10 But if Christ is in you, although the body is dead because of sin, the Spirit is life because of righteousness. 11 If the Spirit of him who raised Jesus from the dead dwells in you, he who raised Christ Jesus from the dead will also give life to your mortal bodies through his Spirit who dwells in you.

During this season of Ordinary Time, we have been exploring what it means to live as a Christ follower. We have revisited many passages where Jesus calls his disciples, instructs his disciples, sends them out and commissions them. The life of a disciple is not a small calling, and it is certainly not a boring or passive one. Our passage today may give us some clues as to why this is.

Romans 8:1-11 is a familiar passage to many, especially the first verse which is loaded with good news. Other portions of the passage have unfortunately left many with some confusion regarding how we understand the difference between living life in the flesh and living life in the Spirit. Hopefully we can clear up some of that confusion along the way. But even if we don’t, we can certainly soak up some astoundingly good news from the first verse. So, let’s begin there.

There is therefore now no condemnation for those who are in Christ Jesus. (Romans 8:1 ESV)

This is a very strong statement as written, but the Greek packs even more of a punch. In Greek, the most important words are placed at the beginning of a phrase. Here the very first word is “no.” Paul wants to be emphatic and bold about the truth he is proclaiming. Perhaps Paul knows our strong tendency to feel condemned and to condemn others.

If condemnation was a rock, we would all probably have a bag full of them. Not to mention a handful in our hands. When we see God as a distant angry god who condemns us, we will walk around carrying rocks of condemnation that weigh us down. In addition to being weighed down we are also tempted to hurl our rocks of condemnation at others. As we tightly quench a rock in our fist, we find that we are unable to receive the grace God gives. But may the Spirit speak to us today through this one little verse that God in no way carries rocks of condemnation around. He does not throw rocks at us, not even a pebble of condemnation. He has on the other hand, sent us his Son, Jesus Christ who is our Rock of Salvation. This Rock does not condemn us; rather, as we will see later, he condemns all that condemns us.

As a follower of Jesus, are there ever times when you feel you have been hit by the cutting and bruising stone of condemnation? If so, this verse tells us unequivocally that neither Jesus nor his Father threw it. Perhaps it came from the hands of a friend or family member — those most often hurt the most. Or perhaps you even got pelted by a weighted down preacher. Unfortunately, the pulpit at times gives one a perceived high ground for stone throwing. Or, more common, maybe the stone was let loose from your own sling only to come back and smack you in the head like a boomerang. Self-condemnation is deceptively punishing. Wherever the source of our condemnation, we need to take these words seriously, “There is therefore now no condemnation for those who are in Christ Jesus.” That means, that if there is no condemnation in Jesus, there is no condemnation.

Jesus is the one who determines reality, not our closest family members or friend, not other authority figures, and certainly not ourselves. Condemnation doesn’t exist for you. That means that when others hurl it your way, they are hurling a lie. It’s an empty rock weighing less than a feather. In this way, Jesus becomes our shield that repels any rocks of condemnation hurled our way.

This is a good scripture to quote when someone attempts to hit you with a condemning stone. You don’t have to receive the blow of something that doesn’t exist. There is no condemnation. And when you are tempted to condemn yourself, you cannot justify your self-condemnation by arguing your case from the evidence of your sins. All that evidence has been nailed to a cross and put to death. Your case in the Father’s courtroom is dead on arrival and will not be heard. So, no need to rehearse it over and over on the way. Paul will make that clear as well. At this point I can hear the protest welling up. Are you saying that it’s OK to sin then? Paul had to deal with that protest as well and he again offers an emphatic “NO!” That question misses the point which Paul will elaborate on in the next few verses.

But before we get there, we should note two additional qualifiers of this extremely good news.

First, there is a qualifying “when.” When will this be that there is no condemnation? Paul again is quite forceful with “now.” We don’t have to wait till we overcome all our sins. We don’t have to wait till Jesus returns. This is a reality that is given to us right now. That’s a hard time stamp to accept when we look at how many times we have been deserving of condemnation.

The second qualifier is, who does this apply to? The answer is, “for those who are in Christ Jesus.” This is Paul’s favorite phrase for speaking of those who put their faith in Jesus, receiving the new life he has for them. It is his way of making the supreme distinction between those who are disciples and those who are not: their union in Christ. That’s where the new life that Paul is going to talk about is found and where we live in the reality where condemnation does not exist.

So, with that, we can move on to the next few verses where Paul is going to talk about the new life believers are brought into. Beware of some confusing and challenging language.

For the law of the Spirit of life has set you free in Christ Jesus from the law of sin and death. For God has done what the law, weakened by the flesh, could not do. By sending his own Son in the likeness of sinful flesh and for sin, he condemned sin in the flesh, in order that the righteous requirement of the law might be fulfilled in us, who walk not according to the flesh but according to the Spirit. (Romans 8:2-4 ESV)

The new life Paul speaks of that we have “in Christ” is a life of freedom. We are set free in Christ. And we are told that this is something “God has done,” so it is a freedom given by grace. We do not earn it in any way. We first see that we are set free from something, namely, “from the law of sin and death.” The two enemies of sin and death no longer have the final say over us. And we are told exactly why.

Jesus was sent to take on all our sin and its penalty of death in order to condemn sin itself. Nice play of words by Paul there. We are not condemned, sin is. So, we are now free from it. But not only are we set free from something; we are set free for something. As Paul puts it, we are set free “in order that the righteous requirement of the law might be fulfilled in us, who walk not according to the flesh but according to the Spirit.” The word “walk” is meant to indicate a way of life. In Christ, we are set free from sin to live a righteous life. What is the point of being freed from sin if we do not walk in that freedom to live in righteousness?

That answers the question about being free to sin on account that there is no condemnation. That would be equivalent to saying we are free to put ourselves in prison. That’s not a description of freedom, but a description of insanity.

Now that Paul has spent some time talking about the new life we have in Christ, he is going to reference the old life we have been delivered from.

For those who live according to the flesh set their minds on the things of the flesh, but those who live according to the Spirit set their minds on the things of the Spirit. For to set the mind on the flesh is death, but to set the mind on the Spirit is life and peace. For the mind that is set on the flesh is hostile to God, for it does not submit to God’s law; indeed, it cannot. Those who are in the flesh cannot please God. (Romans 8:5-8 ESV)

In contrasting the old life with the new life, some confusion has slipped into our understanding of what Paul is saying. He is not speaking of two realities that are warring within us. Rather, he is talking about two different mindsets. The old mindset is focused on the “flesh” and the new mindset is focused on the “Spirit.” And for Paul, the word “flesh” refers to sinful flesh, not our physical bodies. Living in the “flesh” means we are misusing our bodies, but it is not a renunciation of the body itself. So, a mindset focused on the “flesh” is not interested in pleasing God. Therefore Paul can say, “Those who are in the flesh cannot please God.” In contrast, those who have set their minds on the Spirit are led into “life and peace.” That’s the life we have “in Christ.”

Now Paul will conclude with another emphatic statement of reality for those who are in Christ.

You, however, are not in the flesh but in the Spirit, if in fact the Spirit of God dwells in you. Anyone who does not have the Spirit of Christ does not belong to him. But if Christ is in you, although the body is dead because of sin, the Spirit is life because of righteousness. If the Spirit of him who raised Jesus from the dead dwells in you, he who raised Christ Jesus from the dead will also give life to your mortal bodies through his Spirit who dwells in you. (Romans 8:9-11 ESV)

With no questions asked and without reservation, Paul announces to the church in Rome, and to us today, the assurance that we are “not in the flesh but in the Spirit.” The implication is obvious. Because we are those who belong to Christ, Paul is telling us to live in our true identity. To live as if we do not belong to Christ is to forget who we are and to live a lie. And we do this often. So, we need constant reminders of who we are, which is exactly what Paul is giving the believers in Rome – Jew and Gentile alike. He is reminding them of what it means to be in Christ, to belong to him and to his Father.

This is the life we are made for, and by God’s grace we have entered it and can start living it out. And as we live out of our true identity in him, we become a witness to others that they too are invited into this life of no condemnation, a life full of peace and righteousness.

Paul also leaves us with the hope that even our physical bodies, which have suffered at the hands of sin and death, will be raised to new life as well. In Christ, we are redeemed and made whole. There will be no fracture between our mind and body. It will all consist of the same walk, going in the same direction, not being pulled at the seams. There is a lot to meditate on in these passages. We will be hard pressed to even scratch the surface of what this new life in Christ will fully entail. But for certain, we will not be disappointed.

GOING DEEPER

a recap of last week’s Thursday Dive

From The GCI Statement of Beliefs:

“The Son of God is the second Person of the triune God, eternally begotten of the Father. He is the Word and the express image of the Father.”

John 1:1-2 (ESV) In the beginning was the Word, and the Word was with God, and the Word was God. 2 He was in the beginning with God.

How can the Word be God and “with God” at the same time?

John 14:20 (ESV) In that day you will know that I am in my Father, and you in me, and I in you.

This passage speaks to three relationships that are more than just relationships. It speaks to three unions.

-

- “I am in my Father” …. ontological union – the union of Jesus Christ with the two other Persons in the Godhead

- “you in me” …………….. hypostatic union – the union of Jesus Christ with all humans by virtue of his union with human nature …

- “I in you” ……………….. spiritual union – the union of Jesus Christ with some humans by virtue of his union with their persons

(Eph. 1:10; Rom 5:14; 1 Cor 15:22; 1 Cor.15:45-47; 2 Cor. 5:18-20) (Titus 3:5; Luke 2:52; Heb. 5:8; 2:11; John 17:19; 1 Cor. 1:30)

“To learn more about the distinctions between these three types of union, and the related topic of the differences between believers and unbelievers, see GCI’s essay Clarifying Our Theological Vision.”

Clarifying Our Theological Vision, by Gary Deddo

Introduction: Our Journey of Theological Renewal

By Dr. Joseph Tkach

As a denomination, our renewal began in the early 1990s with the transformation of our doctrines. That doctrinal renewal began with a new understanding of the nature of the covenant of grace that God, in Christ, has with all humanity, and how that covenant relates to the provisional Law of Moses and to what Scripture refers to as an “old covenant” and a “new covenant.” Recognizing that Jesus fulfilled the covenant on our behalf (as grace and truth personified), gave us a clearer focus both doctrinally and theologically, with the result being the transformation of our Christology (doctrine of Jesus Christ). By God’s grace we came to understand that Jesus is the center and heartbeat of God’s plan for humankind. In our minds and hearts, we became Christ-centered.

This renewal of our Christology led to asking and answering the vital question: Who is the God revealed to us in Jesus Christ? The answer led us to embrace a theological vision that we now refer to as incarnational Trinitarian theology.

That theology (with “theology” meaning “knowledge of God”) is incarnational in that it is Christ-centered, and Trinitarian in that the God who Jesus reveals to us is a Trinity (one God in three Persons): Father, Son and Holy Spirit. We came to understand that in the fullness of time, God the Father sent his eternal Son into time and space to become human, thus assuming our human nature as the man Jesus Christ. And when Jesus ascended, he raised human nature with him in glory and, with the Father, sent the Holy Spirit to be with us in a new and deeper way. The self-revealing, sending God thus sent us both his Living Word and his Breath.

Our incarnational Trinitarian theology is rooted in Scripture (the New Testament writings in particular) and has been worked out in the writings of teachers in the early (patristic) church including the Didache (a first-century church manual with instructions about baptizing into the one name of the Father, Son and Holy Spirit), and the great Creeds of the church: the Apostles Creed (2nd century), the Nicene-Constantinopolitan Creed (4th century), the Chalcedon Definition/Creed (5th century) and the Athanasian Creed (5th century). Our theology is thus biblical and historically orthodox.

Our understanding of this theology has been greatly aided by the writings of several early church leaders, including Irenaeus, Athanasius and the Cappadocians. We have also found helpful the writings of several 20th-century theologians who, in the providence of God, contributed to a resurgence of interest in this ancient Trinitarian theological vision in many parts of the body of Christ over the past six or seven decades. These theologians include Karl Barth, Thomas F. (TF) Torrance, James B. (JB) Torrance and Ray S. Anderson — men whose faith and understanding traces back to the Bible and to the early creeds of the church. Their understanding also aligns with the central concerns of the Protestant Reformation framed largely by Martin Luther and John Calvin, especially on the matter of grace. We have been (and continue to be) greatly aided in our journey of theological reformation by Dr. Gary Deddo, who stands in this ancient and orthodox stream of theological renewal. We are blessed to have this theologian on our Grace Communion Seminary faculty and, as you probably know, Gary serves as President of GCS and as a special assistant to the GCI president.

Over the last decade or so, as we’ve worked out the many details of our incarnational Trinitarian theology, we’ve used terms in varying ways to communicate its core concepts and precepts. At times, our use of a few of these terms was imprecise, leading to minor points of confusion, particularly in matters related to the nature of the church and the Christian life. For that confusion, we apologize, and now we seek to refine our terms and concepts so that there will be consistency and clarity in our communication. These refinements do not change our core theological convictions, nor the practices that flow from them. We are simply continuing to build on the solid biblical foundation that has been laid, with Christ being its living cornerstone.

To help in the important task of clarifying and refining our theological vision, I asked Dr. Deddo to assemble an Educational Strategy Task Force. ESTF members were Gary Deddo (chair), Russell Duke, Charles Fleming, Ted Johnston, John McLean, Mike Morrison and Greg Williams. All have advanced degrees in theology or ministry, taught at Grace Communion Seminary (GCS) and/or Ambassador College of Christian Ministry (ACCM) and had administrative leadership roles in GCI.

As part of its work, the ESTF identified problems with the way we articulated certain aspects of our theology, and so I asked Dr. Deddo to author an essay titled Clarifying Our Theological Vision to help clarify our theological terms, and thus refine certain key concepts in our theological vision. The goal is greater consistency and clarity in our publications and in what we teach in our courses. I also pray that the essay will help sharpen what we teach in sermons and studies in our congregations.

I’m grateful for the journey God has us on and for where we now are. Have we arrived? No, our journey continues, with its ultimate destination being a new heaven and new earth in which there will be a new Jerusalem (Rev. 21:1-4, 22-23). Thanks for being part of the journey, for your loyalty, patience and willingness to grow in the grace and knowledge of our Lord and Savior Jesus Christ. Thanks also for being a faithful teacher of the glorious gospel of Jesus.

And now the essay from Dr. Deddo.

Part 1: Clarifying Two Key Terms: “All Are Included” and “Union With Christ”

As noted by Dr. Tkach in the Introduction, the goal of this essay is to clarify some of the key terms we use in communicating the wonderful truths of our incarnational Trinitarian faith. As he also notes, though we’re not making significant changes, we are providing some clarifications to help us in our ongoing journey of theological renewal.

All are included

A key understanding of our theology has to do with what God has accomplished for all humanity in and through his incarnate Son, Jesus Christ. For many years, we’ve summarized that understanding with the phrase, all are included (and the related declaration, You’re included). By all we mean believers and non-believers, and by included we mean being counted among those who God, in and through Jesus, has reconciled to himself. We thus mean to say that God has reconciled all people to himself.

This theological declaration is based on the biblical revelation that Christ died for all and that God has loved and reconciled the world to himself (Rom. 5:18; 2 Cor. 5:14; John 3:16; 2 Cor. 5:19, Heb. 2:9). Jesus is “the lamb of God who takes away the sins of the world” (John 1:29), and he is the “ransom” for all (1 Tim 2:4, 6; 4:10; Matt. 20:28). Because this reconciliation is accomplished, and thus a present reality, God’s desire, which is fulfilled by the ongoing ministry of the Holy Spirit, is for all people everywhere to come to repentance and faith so they may personally experience (receive and live into) this reconciliation and so not perish (2 Pet. 3:9; Ezek. 18:23, 32). Thus when we declare that all are included we are affirming several important truths:

- Jesus Christ is Lord and Savior of all humanity

- He died to redeem all

- He has atoned for the sin of all

- Through what he did, God reconciled all people to himself

- Jesus is the mediator between God and all humanity

- He has made all his own by virtue of his redeeming work

- He is for all and against none

- He is judge of all, so that none might experience condemnation

- His saving work is done on behalf of all, and that work includes his holy and righteous responses to the Father, in the Spirit—responses characterized by repentance, faith, hope, love, praise, prayer, worship and obedience

- Jesus, in himself, is everyone’s justification and sanctification

- He is everyone’s substitute and representative

- He is everyone’s hope

- He is everyone’s life, including life eternal

- He is everyone’s Prophet, Priest and King

In all these ways, all people in all places and times have been included in God’s love and life in and through Jesus and by his Spirit. In that we rejoice, and on that basis we make our gospel declarations. But in doing so we have to be aware of some potential for confusion. We must neither say too little or too much about inclusion (reconciliation). Perhaps, at times, we’ve said too much, making inferences concerning the reconciliation of all humanity that the Bible does not support — ones that are neither logically or theologically necessarily true.

It’s about relationship, which means participation

To avoid making unfounded inferences, it is important to note that when the Bible speaks about reconciliation (inclusion), what it is referring to is a relationship that God, by grace, has established in the God-man Jesus Christ between himself and all people. That relationship is personal in that it is established by the person of the eternal Son of God, and it involves human persons who have agency, minds, wills and bodies. This reconciliation involves all that human beings are — their whole persons. Thus this personal relationship calls for, invites, and even demands from those who have been included the response of participation. Personal relationship is ultimately about interaction between two persons (subjects, agents), in this case between God and his creatures.

By definition, personal relationships are interactive — they involve response, communication, giving and receiving. In and through Jesus, God has included all people everywhere in a particular relationship with himself for just these purposes so that what has been fulfilled for us objectively in Jesus by the Spirit, will then be fulfilled in us personally (subjectively) by the Spirit via our deliberate, purposeful participation (response) as subjects who are moral, spiritual agents. What Christ did for us, he did so that the Holy Spirit could work a response out in us.

When we understand that the person and work of Christ establishes or reestablishes a living, vital, personal relationship with all humanity, then the biblical teachings concerning inviting, admonishing, encouraging, directing, commanding and warning in regard to setting forth the fitting or appropriate response make sense. But if the gift of reconciliation (inclusion) is understood as merely a fixed principle, an abstract universal truth (like the sky is blue, or 2+2=4), or as an automatic and impersonal effect brought about through a causal chain of events imposed on all, then the myriad directives in the New Testament concerning our response (participation) make no sense.

The indicatives of grace set us free to respond to the imperatives of grace

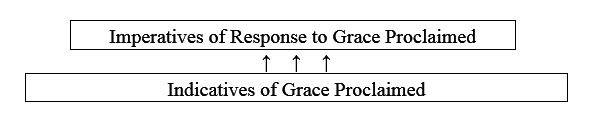

Many proclamations in the New Testament declare the truth of who God is and what he has done for us, including that he, in Christ, has reconciled all humanity to himself. These proclamations are the indicatives of grace, which, by their very nature, call forth and set us free for a joyful response to the imperatives of grace that are also defined in the New Testament. Here is a diagram showing how these indicatives and imperatives are related:

Our responses to the imperatives of grace, grounded in and thus flowing from the indicatives of grace, are made possible only because of the ministry of the Holy Spirit, who continues his work in the core of our persons (our subjectivities) in order that we might respond freely to God and his grace with repentance, faith, hope and love.

The Holy Spirit grants us this freedom to respond (even as we hear the imperatives) by releasing us from the bonds of slavery so that our responses are a real sharing in Christ’s own responses made on our behalf as our substitute and representative — our great and eternal High Priest. This indicative-imperative pattern of grace is found throughout the New Testament. For example, note Jesus’ first proclamation concerning himself and his kingdom (the indicative) followed by the imperative, which defines our response:

Jesus came to Galilee, proclaiming the good news of God, and saying, “The time is fulfilled, and the kingdom of God has come near; repent, and believe in the good news.” (Mark 1:14-15)

Note that the imperative, “repent and believe,” is based on and made possible because of the indicative that “the time is fulfilled … the kingdom of God has come near.” Because of who Jesus is and what he has done, people are given entrance into personal relationship with Jesus as their King and thus can respond by participating in his rule and reign.

At work here is a vitally important truth: because God loves us, he is interested in our response to him. He looks for it, notices it, even tells us the kind of response that is fitting to the relationship he has already given us by grace (through reconciliation). Moreover, by the Holy Spirit ministering to us on the basis of Christ’s completed work, our Triune God has even provided all we need to make that response. We never respond autonomously, simply on our own. Instead, by the Holy Spirit, we are enabled to begin sharing in Jesus perfect responses that he makes for us as our eternal mediator or High Priest.

Avoid two errors

There are two common errors in thinking about the indicatives and imperatives of grace. The first is to regard the indicatives proclaimed in the New Testament as fixed, impersonal principles or abstract laws — general and universal truths operating like the mechanical, so-called laws of nature, or perhaps of mathematics.

The second error (which often accompanies the first) is to regard the imperatives mentioned in the New Testament as sheer, externally imposed legal obligations that indicate the potential ways we can condition God to act or react to us in some way. Embracing that false notion, we are tempted to think of the imperatives as setting forth terms of a contract with God: if we do certain things (fulfill certain contractual obligations) we will bring to pass the responses from God that we desire and to which he has contractually agreed.

Both of these errors presume legal, mechanical, cause-and-effect, force-vector-like actions and reactions instead of what is found in a real personal relationship. These errors reflect thinking that is not grounded in the covenant of grace by which God has freely established a relational reality with humankind for the sake of dynamic, personal and interactive participation, communication, communion, fellowship — what the Greek New Testament calls koinonia.

We err when we imagine we are somehow coerced slaves to God and to his imperious ways, or when we imagine we can manage a contract with God where we attempt to negotiate terms of mutual obligation agreeable to both parties. Such imaginings are not how God operates. He created us for real, personal relationship in which we participate, by grace, through Christ and by the Holy Spirit. All our responses are real participation in an actual relationship—the relationship God has established for us for the sake of koinonia (fellowship, communion) with him in dynamic, personal ways—the ways of freedom in love.

We did not establish this relational reality by our responses. Only God can create the relationship, and so he has, on our behalf in and through Christ. Note, however, that though our personal responses create nothing, they do constitute real participation in the relationship God has given us in Christ. These responses are made possible by the freeing and enabling ministry of the Holy Spirit, based on the vicarious ministry of Jesus. We have been included, through Christ and by the ministry of the Spirit, in a saving, transforming and renewing relationship with God — a relationship that calls for our response.

With this clarification in mind, we can see that we must not use the phrase all are included to say too little or too much — and perhaps, at times, we have said too much. Yes, all humanity has been included in a saving, transforming and renewing relationship with God (referred to in Scripture as reconciliation with God). But this particular kind of inclusion in Christ is not a fixed, impersonal, causal and abstract universal “truth” that is divorced from real relationship. In fact, reconciliation is specifically for the sake of our response, and so it is for real, personal relationship.

What we can say is this: all have been reconciled(included) but not all are participating. The God-given purpose of this relationship, established through reconciliation, cannot be fulfilled in us as long as there is little or no participation in the relationship — if there is resistance to and rejection of the relationship that has been freely given to us. The full benefits of the relationship cannot be known or experienced by us if we do not enter into it — if we are not receptive to it and its benefits.

Thus we must account for the difference between participating in the relationship, according to its nature, and not participating, thus violating its nature and purpose. Non-participation does not negate or undo the fact that God has reconciled us to himself (that he has included us in the relationship he has established, in Christ, with all humanity). To deny this reality does not create another reality. Going against the grain of reality does not change the direction of the grain, though it might gain us some splinters! We have no power to change the grain.

A good example of the difference between participation and non-participation is the elder brother mentioned in the parable of the prodigal son. He refused to participate—to enter the celebration the father established and invited him into. Note also this example in the book of Hebrews:

For we also have had the good news proclaimed to us, just as they did; but the message they heard was of no value to them, because they did not share the faith of those who obeyed. (Heb. 4:2)

This personal and relational understanding of receiving the gift of grace freely given us by the whole God (Father, Son and Spirit) helps clarify many things in the New Testament that otherwise would seem inconsistent or even incoherent. To think otherwise (in mechanical or causal ways) would be to ignore, or (worse) to dismiss, whole swaths of biblical revelation. A personal and relational understanding of God’s grace helps make sense of the proclamation of the indicatives of grace and the proclamation of the imperatives of grace, the latter being the call to receive and participate in the gift of the relationship established in Christ that is being fulfilled by the Holy Spirit.

Union with Christ

Having looked at the term all are included (which pertains to the reconciliation all humankind has with God in Christ), we now can look at a related biblical teaching that also needs clarification — the term here is union with Christ. As with reconciliation, we err if we view union with Christ as a fixed, generic and abstract principle, rather than the dynamic, covenantal and relational reality that it is. In making that error it’s easy to erroneously equate the concept of the reconciliation (inclusion) that all humanity has with God in and through Christ with the concept of union with Christ.

Though some assume that all who God has reconciled to himself in Christ are automatically in union with Christ, there are significant problems with this assumption — problems that have become more apparent to us over the last four or five years as pastors have sought to teach about union with Christ and/or church members have tried to understand the concept. Because of these problems, we’ve spent time in further investigation of the biblical teaching and we’re now addressing those problems by providing this additional teaching (via this series of articles) on this important topic.

First, it’s important to note that the New Testament never equates reconciliation (universal inclusion) and union with Christ. The truth that Christ, who died for all, is everyone’s Lord and Savior, does not mean that everyone is united (by the Holy Spirit) to Jesus. Union with Christ, as that term is used in the New Testament, is limited to describing those who are receptive, responsive and thus participating by the Holy Spirit in the gift of relationship with God established by Jesus Christ. This delimited description of union with Christ also applies to other closely related New Testament expressions including being “in Christ” or “in the Lord.”

While God intends union with Christ for everyone on the basis of the atoning, reconciling work of Christ, not all have received that union or have entered into it. In that sense not all are united to Christ, not all are one with Christ, not all are “in Christ,” not all “have the Son” (1 John 5:12), and not all “have the Spirit of Christ” (Rom. 8:9).

None of this means that God is separate from, or has rejected non-believers. It does not mean that God is against them, has not forgiven them, has not accepted them, or does not love them unconditionally. It simply means that such persons are not yet participating in (or possibly are resisting) the work of the Holy Spirit, whose ministry it is to open the minds of non-believers to the truth of the gospel, unite them to Christ, and call forth a response of repentance and faith befitting that union. In the end, “Everyone who calls upon the name of the Lord will be saved” (Joel 2:32; Acts 2:21; Rom. 10:13; Ps. 86:5), though not all (yet) are calling on the Lord.

In the New Testament, union with Christ cannot be separated from participation in Christ or from communion or fellowship (koinonia) with Christ. Union with Christ, understood properly, is about personal relationship, and is thus limited to those who are participating in the relationship God has given us by grace. As James B. Torrance used to summarize it: union with Christ cannot be separated from communion with Christ. These twin doctrines cannot be separated even though they can be distinguished.

We must not think of union with Christ in fixed, mechanical, objective and impersonal ways, assuming that non-believers are automatically united with God, in Christ, in the same way as believers (who by definition, are participating by their believing, their faith). To do so would be to separate union with Christ from participation with Christ. If we are to follow the mind of Christ as found in the New Testament, we should reserve “union with Christ” and being “in Christ” as ways of describing those who, by the Spirit, are participating, receiving and responsive to Christ and his word. Participation does make a difference, though it does not make all the difference. It doesn’t, for example, change God’s mind or his intention or desire. However, our way of speaking and our theological understanding ought to be able to communicate the difference participation does make, and do so in ways that match the biblical ways of speaking.

Faithfully and accurately proclaiming the gospel

Carefully and closely following the biblical patterns of speech and thought will help us communicate the truth and reality of the gospel of Jesus Christ with consistency, clarity and biblical accuracy. It will also help us avoid contributing, even inadvertently, to confusion or hesitation about the truth of union and communion with Christ by the Spirit.

We should avoid, therefore, using the term all are included as an umbrella phrase that tries to say everything there is to say about salvation. What Scripture consistently means when speaking of union with Christ is not the same as what we mean to say in using the phrase all are included, which as we’ve seen, pertains to the gift of universal reconciliation.

Though in Acts 17:28 the apostle Paul (quoting a pagan philosopher known to his audience) says that “in him [God] we [all humans] live and move and have our being,” he is referring to the created state of all humans and not to union with Christ — a concept he develops elsewhere to refer to the reciprocal, personal relationship that exists, through the Holy Spirit, between God and believers (Christians).

Not properly distinguishing between all humanity having been reconciled already to God in Christ (and thus included) and the believer’s union with Christ, confuses or conflates biblical terms and thus risks the following:

- The loss of most or all of the full understanding of the personal, dynamic and relational nature of the gift of salvation in relationship with the living, triune personal God.

- The loss of the fact that the gift of salvation involves the ongoing ministry of the whole God: Father, Son and Holy Spirit.

- Turning what is dynamic and relational into something non-relational, generic, impersonal, causal and a fixed fact or data point that does not necessitate (in a vital way) the continuing ministry of the Holy Spirit in the life of the members of the church, the body of Christ.

Our incarnational Trinitarian faith is grounded in the gospel of Jesus Christ, not a gospel of universal inclusion (where “inclusion” is used as an umbrella term to speak of all aspects of salvation). We proclaim the good news about the relational nature of the gift of grace that God, in Christ, and by his Spirit, freely gives us. Inclusion is one aspect of that gospel, but not the whole of it.

Two related, but distinct unions

This brings us to another point that needs clarification, as it too has contributed to some confusion or hesitation. In accord with the gospel of Jesus Christ, we rightly distinguish between two types of relationship, which, theologically, have both been referred to as unions, but when carefully treated by theologians are distinguished by qualifying each with a different accompanying term. The problem here is not so much one of biblical usage as discussed above, but one of how union is used in theological formulations. In the latter case, many overlook the important theological qualifications made and assume all unions involving God are identical, when they are not. The problem is made greater when an improper notion of inclusion is conflated with either or both of these notions of union.

The hypostatic union

The first union pertains to what theologians refer to as the hypostatic union. This is the union of divinity (divine nature) and humanity (human nature) in the one person (hypostasis) of the God-man Jesus Christ at his incarnation. It should be noted that this union does not amount to a fusion or confusion of these two natures, but a joining together that maintains their distinction while bringing about a true relationship and interaction between them under the direction of the subject of the eternal Son of God. (This theological understanding goes all the way back to the Chalcedonian Definition/Creed of the 5th century.)

This hypostatic union pertains to all people since the human nature Christ assumed is common to all humankind—both believers and non-believers. Human nature, with all its attributes (mind, will, affections, etc.) has, in Christ through his life, death, resurrection and ascension, been regenerated, justified, sanctified and glorified. On that basis, God, in and through Christ has brought about the reconciliation of all humankind with himself. As a result, God holds nothing against humanity or human nature. In that way, Christ is the first-fruit or first-born from the dead and is the new head of humanity (the new Adam, to use Paul’s terms). Jesus has become the beginning of a new humanity. Thus we can say that there is a right way to say “all are included” meaning “all humans have been reconciled” on the basis of the renewal of human nature itself in Christ.

This understanding is why T.F. Torrance can assert that all are “implicated” (included) in what Christ has done, or that all humanity has been placed on a whole “new basis” in what Christ has done. Likewise, Karl Barth can assert that on the basis of the hypostatic union of the two natures in Jesus, all people are “potentially” Christians—“potentially” members of the church or body of Christ; or all can be considered “virtual” Christians (even if not actual Christians); or that all have been saved in principle by Christ (de jure) but not all are saved in actuality (de facto). These theological understandings parallel the New Testament understanding of Christ being all in all, but also recognizing that not all are participating in that relational reality—not all are believing, not all are responding to or are receptive of this reality. Not all are worshipping God in Spirit and in truth. Not all are active witnesses to Jesus Christ. And in that sense, not all are actual Christians.

The spiritual union

The second kind of union of which theologians speak pertains to the spiritual union that, by the Holy Spirit, unites believers with God in a particular type of relationship. The New Testament refers to this kind of union as “union with Christ”—a union and communion with God, in Christ, by the Holy Spirit. In this kind of union there is an essential recognition of a distinct, though not separate, ministry of the Holy Spirit to bring it about. After the incarnation and the earthly work of Christ, the Spirit is sent on a special mission, or for a special ministry, that is only now possible on the basis of the completed work of Christ accomplished with or in our human nature.

By this follow-up ministry of the Holy Spirit, individuals and groups of persons are freed and enabled to repent and believe, and have faith, love and hope. They are able to enter into a worship relationship with God “in Spirit and in truth.” By the Spirit, persons are incorporated into the body of Christ as they respond (participate), typically by baptism, confession of faith, participation in communion (the Lord’s Supper) and in Christian worship where they receive instruction and put themselves under the authority of the apostolic-biblical revelation. The spiritual union thus designates participation by the Spirit in the renewed human nature Christ provides for us so that we might participate in right relationship with God through him, by the Holy Spirit.

It is also important to note that in this union and communion with Christ, by the Holy Spirit, we do not become one in being with Jesus Christ—we do not become Jesus, and he does not become us. Union and communion with Christ is not a fusion or confusion of persons—it is a personal and relational union or unity, which necessarily includes a participation that maintains the difference of persons, the distinction of subjects (or personal agencies). While the work of Christ reaches the very depths of who we are (our being or ontology), the ontological difference of persons is not erased in our union with Christ. We are not absorbed into Jesus, nor into the being of God. Thus the relationship between the two persons at the deepest (ontological) level of who we are remains a real relationship, with real participation and fellowship maintained.

Summary

With these thoughts in mind, we now can summarize our key points:

- God has reconciled all people (believers and non-believers) to himself in Christ. All people have been implicated in the hypostatic union of divinity and humanity brought about through the Incarnation of the Son of God.

- Through the ministry of the Holy Spirit, believers are brought into the spiritual union of God and humanity, and thus are “in Christ” by virtue of their positive, Spirit-enabled response to (participation in) the relationship created by the hypostatic union.

- Not all are included in the spiritual union since not all are participating in the saving relationship. Not all are included in that sense, even though the hypostatic union in Christ was accomplished for the sake of the spiritual union that would be brought to fullness through the ministry of the Holy Spirit.

- The goal of the hypostatic union is thus fulfilled in the spiritual union, brought about by the Holy Spirit as persons participate in the relationship begun in the reconciliation of all humanity to God in and through the hypostatic union of God and humanity in the person of Jesus Christ.

- In our gospel declarations, we need to account for both types (or perhaps we could say both phases) of union, noting that both are aspects of the outworking of our salvation involving the work of the whole Triune God (Father, Son and Spirit).

- We can rightly use the phrase all are included when referring to the hypostatic union (the first phase). In doing so we should note that human nature was joined (but not fused) to Christ, and thus included in his whole mediatorial ministry of learning obedience, overcoming temptation, ministering under the direction and power of the Holy Spirit, submitting to the righteous judgment of God on the cross, and in the resurrection of our human nature with him in his resurrection and raised up to glory in his ascension.

- As we use the term inclusion to refer to the hypostatic union, it’s vital to remember that the purpose of this inclusion is personal relationship. Via the hypostatic union, God, in the person of the God-man Jesus Christ, has graciously reconciled all humanity to himself. All people (believers and non-believers) are, through the hypostatic union, included in a relationship with God for the purpose of personal participation — a personal response of repentance, faith, hope and love.

- We should be careful to not talk about inclusion (which pertains to the hypostatic union) in ways that obscure or make seem minor the matter of the Holy Spirit’s ministry and the related matter of our participation and response to God, both of which pertain to the spiritual union.

- The difference participation makes holds out hope of renewal and transformation for those who have not yet turned to Christ. It also provides insight and motivation for those who have begun to participate but who have grown weary or might be tempted to return to their old ways of non-participation. That’s the point of the many admonitions in the New Testament to continue living in relationship with and thus to turn back to Christ. That’s the point of its warnings to not resist the Spirit.

- If we fail to uphold the differences that participation does make, we will be unable to talk accurately about the differences it does not make, namely that though we be faithless, God remains faithful (2 Tim. 2:13).

- In our preaching and teaching we must account for both types of union, carefully explaining the importance of participation which relates to entering into deliberate, personal relationship with God, since that’s what God has provided so richly for us. We need to preach and teach together both the indicatives of grace and the imperatives of grace that call for and enable our fellowship and communion (koinonia) with God, through Christ, by the Holy Spirit.

Conclusion

Because our Triune God, who is love, is interested in us, he wants to have with us a real, actual, living, loving, vital relationship. Through the hypostatic union of God and humanity in the person of Jesus Christ, God reconciled all humanity to himself precisely so that humans may have a worship relationship with the Trinity. Now, God, in Christ and through the Spirit’s ongoing ministry, is drawing believers into a spiritual union (union with Christ) that involves participation (response, sharing in, living into, communion). In this koinonia there is a difference between those participating in God’s free gift of relationship (established in the hypostatic union) and those refusing to participate, or who have not yet begun to participate. That’s why, in the New Testament, the term “union with Christ” applies to persons in a posture of responding in the Holy Spirit, and not to persons in a posture of resisting or ignoring the Holy Spirit. That is why receiving what is freely given is often emphasized in Scripture, as seen in these verses:

- [Jesus is sending Paul] to open their eyes so that they may turn from darkness to light and from the power of Satan to God, so that they may receive forgiveness of sins and a place among those who are sanctified by faith in me. (Acts 26:18)

- All the prophets testify about him that everyone who believes in him receives forgiveness of sins through his name. (Acts 10:43)

- If, because of the one man’s trespass, death exercised dominion through that one, much more surely will those who receive the abundance of grace and the free gift of righteousness exercise dominion in life through the one man, Jesus Christ. (Rom. 5:17)

- Repent, and be baptized every one of you in the name of Jesus Christ so that your sins may be forgiven; and you will receive the gift of the Holy Spirit. (Acts 2:38)

Given this biblical emphasis and language, it would be unwise to equate the term inclusion (which speaks to the hypostatic union and thus to reconciliation) with the term union (as in “union with Christ” or being “in Christ” or “in the Lord”). Besides departing from the ways the Bible uses these terms, equating the two collapses the biblical distinctions between the hypostatic union and the spiritual union, thus leading to confusion, including obscuring or avoiding the personal and relational nature of salvation which calls for our participation by the Holy Spirit.

The hypostatic union in Christ is not the same as our spiritual union with Christ by the Spirit. Even though they cannot be separated from one another, they must be properly distinguished. Hopefully, it is now clear why, when speaking theologically of these two unions, we must carefully qualify each (as do careful theologians) so as to avoid confusion.

To reiterate this important point, in the New Testament, union with Christ (spiritual union) necessarily involves participation (koinonia, also translated communion or fellowship) with Christ. Why? Because the New Testament uses the word union to speak not of the hypostatic union (related to the vicarious humanity of Jesus), but of the spiritual union (union with Christ).

This spiritual union is not automatic — it is not impersonal or mechanically caused by the hypostatic union. If it were, that would make the full ministry of the Holy Spirit unnecessary, contrary both to how the New Testament depicts the Spirit’s ministry and how it describes the explicit purpose for which the Son sends the Holy Spirit in the name of the Father.

That being said, it’s important to note that the spiritual union is absolutely dependent upon the hypostatic union, wherein the eternal Son of God, via the Incarnation, assumed to himself our human nature (the nature common to all humanity). However, the phrases “union with Christ,” being “in Christ” or “in the Lord,” being members incorporated into “the body of Christ” (the church), being “indwelt” by the Holy Spirit, and being “born again” as a “child of God” are all phrases or terms the New Testament uses in a way that includes (and thus presupposes) the idea of participation—that is, communion with Christ through the Spirit, which is about living in active personal relationship with Christ as a member of his body, the church. Said another way, these particular phrases are reserved in the New Testament for Christians (believers). We believe it is important that we use these phrases in the way the New Testament uses them, not assigning to them different meanings (as do some Trinitarian authors).

We’ve raised several issues in this lengthy article, and we’ll add further detail as this series unfolds. Some of the issues that we will be addressing more fully are the vicarious humanity of Jesus, and what union with Christ entails.

Part 2: Union With Christ, Christ’s Vicarious Humanity and the Holy Spirit’s Ministry

In this part of the essay, we’ll fill out what we covered in Part 1 concerning union with Christ and the vicarious humanity of Christ. We’ll then look at the ministry of the Holy Spirit and the related topic of the biblical distinction between believers and non-believers. These topics are of great importance to our understanding of incarnational Trinitarian theology.

Union with Christ

As we noted last time, the New Testament uses union with Christ to refer exclusively to the relationship the Triune God has with believers. We want to stick with that biblical usage, avoiding statements that imply that union with Christ pertains to non-believers. At times, we made that mistake, referring, for example, to the journey from non-believer, to new believer, to mature believer as progressing from union to communion with God. We also mistakenly said that all are in union but not all are in communion. Both statements are problematic for several reasons:

- The New Testament correlates union and communion so closely that they can be used interchangeably to refer to the same relationship. Although they can, and ought to be distinguished, they can never be separated.

- Though the New Testament declares that God loves all and is reconciled to all, it does not speak of all people as being in union with God in that particular way. The New Testament consistently uses union with Christ to speak exclusively of the relationship that believers have with God.

- The New Testament declares that, through his post-ascension ministry, the Holy Spirit frees and enables people to receive God’s gifts of repentance and faith (belief) and so to become believers. By the continuing ministry of the Holy Spirit, those who are believing begin to share (participate) in all that Christ has accomplished for all humanity, including his ongoing intercession for us so that we might share in the perfect responses he makes for us, in our place and on our behalf. The Holy Spirit’s ongoing ministry is personal and relational, not mechanical or impersonal. It is not a causal fact, nor a general universal principle that is abstractly effective upon all equally. The Holy Spirit unites believers to Christ, incorporating them into the body of Christ (the church) for personal, relational participation (sharing) in the life of Christ.

Not a universal union

The mistakes we made in using the term union with Christ largely resulted from not realizing the potential for confusion when following the writings of some Trinitarian theologian-authors who refer to the Incarnation as creating, through Jesus’ vicarious humanity, a universal union of God with humanity in Christ (universal in the sense that it includes believers and non-believers). In their way of stating it, this universal union came about through what happened when the Son of God, via the Incarnation, assumed human nature. They thus equate union with Christ with the uniting of human nature with God via the hypostatic union.

Unfortunately, this confusion of terms leaves the false impression that the Incarnation itself resulted in all persons having an identical relationship with God—one more or less automatic and causal (and thus objective, in that sense). But that is not what the New Testament teaches in using the term union with Christ, and it is not what we believe and seek to teach.

Union with Christ (and related terms such as in Christ or in the Lord) as used in the New Testament, indicates a depth of relationship that, by the Holy Spirit, is reciprocal and interactive—a personal relationship possible for us individually only on the basis of the objective work of Christ who sanctified, personalized and brought into right, subjective, responsive relationship the recalcitrant human nature that he assumed, via the Incarnation, to himself.

The distinction between believers and non-believers

Misunderstanding union with Christ, some wrongly conclude that there is little, if any, difference between a believer and a non-believer, or at least that whatever we say of a believer should also be said of a non-believer (in the same way). For example, some conclude that all people automatically are united to Christ in the same way. But the New Testament consistently differentiates between those participating in (receiving, responding to, sharing in) the love and life of Christ (the New Testament calls them believers), and those who are not-yet participating (we call them non-believers, though we might appropriately refer to them as not-yet believers).

The erroneous conclusion that both believers and non-believers are in union with Christ results largely from not taking into account that the hypostatic union, which has to do with the union of divinity and humanity (two natures) in the one Person of Jesus, is not equivalent to or identical with, or does not automatically result in, the spiritual union brought about by the Person and work of the Holy Spirit (who ministers on the basis of the Person and work of God in Christ).

In all cases where the New Testament refers to union with Christ (and equivalent phrases) it is referring to this spiritual union, not to the hypostatic union. For our teaching and preaching to align with the Scriptural usage, it’s best we limit our use of union with Christ to refer to the spiritual union—the relationship between God and believers by the post-ascension ministry of the Holy Spirit. This does not mean that we must lead with and thus emphasize that non-believers are not yet united to Christ in the same way believers are. It also doesn’t mean we must try to figure out who is and who isn’t united to Christ, or determine where, on some kind of continuum, each person stands with God. These are not the reasons to hold to the distinction the New Testament makes between believers and non-believers. These would, in fact, be misuses of that distinction. Any distinctions we make must be made for the same reasons the New Testament makes them. Otherwise we fall into another error—an arbitrary, impersonal legalism.

The New Testament distinguishes between believers and non-believers for the purpose of holding out hope to those who are not yet participating, to warn those who are persistently resisting participation, to encourage those who have been participating to keep on, and to highlight all the benefits of participating as fully as the grace of God enables—benefits to oneself and to others, both believers and non-believers. Even more so, making this distinction gives God the glory for enabling us, through the Son and by the Holy Spirit, to enter into a personal, dynamic, responsive and loving communion with him in a relationship of worship.

Our message and emphasis should always begin with and continue to emphasize who God in Christ is, and what he has done for all—what theologian JB Torrance calls the “unconditional indicatives of grace.” Building on that foundation, we can then spell out, as does the New Testament, the “unconditional obligations of grace.” Our message is thus Christ-centered and grace-based, not human experience-centered and law-based.

The vicarious humanity of Christ

Let’s now shift a bit to consider again the topic of the vicarious humanity of Christ, which is related to the hypostatic union but focuses on the essential purpose of Christ’s assumption of our human nature. Together, these truths tell us that Jesus, being fully God and fully human (the divine and human natures being united in the hypostatic union), is in his humanity (human nature joined to his Person) our representative and substitute — the one who, in his humanity, stands in for us. He acts in our place and on our behalf as one of us.

What Jesus did (and still does) in his humanity, he did (and does) for us, in our place and on our behalf as one of us. Jesus was baptized for us, overcame temptation, prayed, obeyed and suffered for us. He died for us, rose from death, and ascended to heaven for us—clothed, as it were, in our humanity. That is what Jesus’ vicarious humanity is all about. It’s a powerful, consequential truth—the gospel in a nutshell. However, it does not tell us everything about our salvation and our relationship with God through Christ and by the Holy Spirit. There is more to the story and so our preaching and teaching must tell the whole story, not just a part. And the parts should fit together, as they do in the biblical revelation.

Filling out the story in no way denies the reality of what can be called the cosmic (or universal, meaning everywhere throughout the universe) implications of the Incarnation, by which the eternal Son of God assumed human nature on behalf of all humanity, and through his vicarious humanity (representing and standing in for us all) reconciled all humanity in himself to God. Indeed, in and through the vicarious humanity of Jesus Christ, who is Lord and Savior of all, all have been reconciled to God—all have been forgiven, no exceptions. It is on this basis that we rightly declare that all are included!

The spiritual union involves participation

Though God has reconciled all humanity to himself in Christ, it is those who are participating in (sharing in) that universal, cosmic reality who are said in the New Testament to be in union with Christ living in relationship with God in what we refer to as the spiritual union. The New Testament calls these believers children of God, noting that they are indwelt by the Holy Spirit in a particular way, having been born from above (or born again, as some translations have it). This participation is the gracious gift of God, in Christ, through the ministry of the Holy Spirit, and not something of our own making or something we have earned. Participation is not a way of qualifying for union with Christ—it is the way of receiving and sharing in the reconciliation we have already with God, in Christ.

This is why Paul says in 2 Corinthians 5 that God has reconciled the world to himself, then immediately adds that those who are members of Christ’s body (the church) are ambassadors called to tell others to “be reconciled to God” (2 Cor. 5:18-20). Paul is not contradicting himself. Because God “has reconciled” all, then all are called by that fact to act, live and so “be reconciled.” Paul is revealing the full story of salvation, of our real relationship with God that involves receiving and responding by the Holy Spirit to the gift freely accomplished and given by God through Christ and personally delivered to us by the Spirit.

Three unions

In part 1 of this series, we mentioned two unions addressed in the New Testament: the hypostatic union (that unites divinity and humanity in the one person of Jesus) and the spiritual union (the believer’s union with Christ by the ministry of the Holy Spirit). We can now mention a third union that also is of great theological importance—theologians call it the ontological union (with “ontological” meaning “pertaining to being”). This is the union between the Father, the Son and the Holy Spirit by which the three Persons of the Trinity are eternally one in being (substance or essence).

This ontological union of the divine Persons does not mean that there are no distinctions between them within the one being of God. The one God is not an undifferentiated ontological monad or lump. The ontological union is a unity of distinguishable divine Persons with distinct names and relationships with each other. As stated in the Athanasian Creed, God is unity in trinity and trinity in unity. C.S. Lewis put it this way: God is tri-personal. We could also say that the unity of God is a triunity.

This ontological union (explored in the excursus below) applies only to the Trinity. It is only in God’s being that there can be three distinct, divine Persons so related that they are one in being. This sort of unity of being is not found in the other two unions, which both involve human nature. In the hypostatic union, the human and divine natures are united in the one Person of Jesus, but those natures are not one in being, they remain distinct in their respective natures. In the spiritual union, human believers are united to Jesus, but the two are not one in being. We humans remain distinct persons. The ontological union is thus absolutely unique as noted in the excursus below.

………………………………………………………………………………………………………

Excursus on the ontological union

Starting with the eternal Trinity, which Jesus tells us about, we recognize a kind of dynamic permanence, stability and faithfulness in our Triune God for all time. There never was a time within the eternal triune life of God when the Father did not love the Son, the Son did not love the Father and the Spirit did not love or indwell the love of the Father and the Son. Jesus says the same in noting that the Father and the Son know and glorify each other, which we can assume (based on other things revealed) involves the Holy Spirit. These are permanent relationships occurring within the one, Triune God. We can also say that the divine Persons share in one Triune mind and will. There never was a time when they were separated in mind or will, or a time before they came to agree, cooperate and become united in will or mind.

These dynamic relationships constitute God’s eternal character, nature and being. God was Triune before there was anything existing other than God and would be Triune even if creation never existed. God alone is uncreated and has existence in himself. God is not dependent upon anything else to exist and to be fully and completely the God that he is — the “I Am” revealed to Moses.

The triune God is loving in his being as a fellowship and communion that is eternal and internal to God. How that is so is something to ponder—a mystery we cannot ever get to the bottom of because God is the incomparable one—one of a kind. This being the case, we can only know God by his self-revelation and not by comparison with other created things (which would lead to idolatry and mythology). That means that when God acts towards that which is not God, namely everything else that exists, we cannot think of that relationship in the same way we think of the triune being and relationships within God. When God acts towards creation to create it or to save it, that act occurs by the gracious will of God—it happens by his choice, his election, in the freedom of his love.

Nothing God does external to his being is necessary to God’s being. Creation and redemption are the free and gracious acts of God towards that which is not God, but which are the products of God’s free willing and acting or making. God acts towards creation not “by nature” but “by grace.” All such relationships are external to God (ad extra as theologians say). They are not eternal, not automatic, fixed, necessary or permanent.

Some of the things God creates including impersonal things like rocks, are more fixed or static and law- or principle-like than are other things, such as human persons who are created in God’s image. But none of these things are identical, and none exist on their own. Human persons are not emanations from (extensions of) or parts of God. Persons are works of God’s grace, by creation and redemption, created as moral and spiritual persons for personal relations in fellowship and communion with God. As humans, we exist contingently and dynamically in personal relationship with God. We are entirely dependent upon God for our ongoing existence, though God is not dependent upon us (or any other part of his creation) for his ongoing existence.

As human beings in relationship with God, we have the capacity to live in personal, moral, spiritual relationships with others, God included. In those relationships we can reflect something of God’s internal and eternal relationships—we can love. And so Jesus lays it out simply, maintaining the difference and similarity of relationships. His use of the word “as” indicates a certain comparison, but not an identity when he says, “As the Father has loved me, so I have loved you.” This indicates the Triune relationship (the ontological union) and the hypostatic union and saving work of Christ. He then goes on to say, “As I have loved you, you ought to love one another.” This command speaks of our human relations being like or similar to Jesus’ relationship with us.

The apostle John, speaking of our relationship to God, says this: “In this is love, not that we loved God but that he loved us and sent his Son to be the atoning sacrifice for our sins.” He also says, “We love because he [God] first loved us” (1 John 4:10, 19). Note here that there is a difference of love, indicated by the order and priority of God’s love over ours. John is referencing the great asymmetry between God’s love and our love, but in this asymmetry there is not a separation, a disconnection. Our love is dependent upon God’s love; our love has its source in God, who is love, and not in ourselves. We then say that our love is contingent upon God’s love, but his love is not contingent upon ours.

If we make the error of thinking that we are somehow fused or one in being with God (even if that fusion were accomplished through some kind of fusion with Jesus), we would be wrongly concluding that our relationship to God is identical to Jesus’ internal and eternal relationship to the Father and the Holy Spirit, rather than distinct and comparable. We would be wrongly imagining that our human persons are so fused with God or with Jesus that we would be essentially indistinguishable as human persons from the Triune Divine Persons — we would thus be a sort of fourth member of the Trinity.

Though failing to distinguish between the three unions and mistaking fusion for union may seem like only small technical errors, the reality is that they make total nonsense of the entire story of God’s salvation by grace, including the real relationship between God and human beings. And so we must carefully avoid making these errors.

………………………………………………………………………………………………………………

Three moments of salvation

Understanding the three unions, and thus grasping that our relationship with God (the Source of our salvation) is in the Trinity, we can now fill out the story of God’s saving grace noting that the Bible speaks of the activity of all three Persons of the Trinity united to work out our salvation. This is also indicated by the fact that the New Testament says we have “been saved,” are “being saved,” and will “be saved.” These past, present-continuing, and future tenses speak of one work with three moments (see the note below) — three aspects of the one saving event.

Note: As in physics, a moment is not an interval of time, but is timeless. It is a moment in time, but has no duration itself. So by analogy, God works timelessly within our time. The one work of the Trinity seems to involve a time sequence for us who live in time, but the three moments of God’s work are not strictly separate or divided, rather they are united in the one saving activity of God. One day, even our view of time will be transformed when we participate fully in time’s perfection, when we have our being in the new heavens and earth and in a new and renewed time and space, in what we now call eternity.

These three distinct (though not separate) moments loosely correspond with the three distinct (though not separate) ministries of the Persons of the Trinity. In Scripture we find that one of the divine Persons is primarily, although not exclusively, associated with a particular moment. We might say that one Person takes the lead or makes a unique contribution to the one saving action towards his time- and space-bound creation and creatures. These distinct actions of the Persons then contribute to the three distinct moments in God’s united, saving work. But we must remember that all the Triune persons act indivisibly, in unity, as they each share distinctively in one Triune divine mind and will.

Note also that these three moments are not exhaustive descriptions of all that the whole God or the Persons do towards creation. They indicate distinct moments of ministry involving the central work of God’s saving activity. The first moment involves the ontological union of the Trinity in relation to salvation. The second, which pertains to the hypostatic union, involves the Incarnate Son’s relationship to our salvation. The third moment, which pertains to the spiritual union, involves the Spirit’s relationship to us in our salvation. These three moments can be summarized as follows:

- The moment of the Father’s decision—the decision to save, made “before the foundation of the world,” anticipating the involvement of the Son and the Holy Spirit by their being sent by the Father.

- The moment of the Son’s work—his saving work, accomplished through his incarnate life, including his earthly ministry, suffering, crucifixion, resurrection, ascension and sending of the Holy Spirit.

- The moment of the Holy Spirit’s work —a work involving bringing about, freeing, empowering and guiding the ever-growing participation of believers (via their personal response, receptivity, decision) to Christ’s work. This work of the Holy Spirit began with the formation of the church after Christ’s earthly work was finished, though it will be complete only with our glorification on the other side of our death.

It’s important to avoid reducing salvation to one of these three moments. Modern western churches tend to do that, almost to the exclusion of the other two. However, some make the opposite mistake of fusing (confusing or conflating) the three moments. We must be careful to uphold the truth that the one, indivisible work of God involves three distinguishable moments in God’s relationship to us in time and space, flesh and blood. We must be careful to uphold both their connection (unity) and their distinction (without any idea of separation).

Union of persons does not mean fusion of being